Expert interview with Karl H. Richter:

Bio: Co-founder of EngagedX, which specialises in providing consultancy, thought leadership, advocacy and policy work. Works internationally across private, public and social sectors. Experienced entrepreneur, leader, and executive. Lectures at the Frankfurt School of Finance and Management.

Previously served a 12 month assignment as Head of Research and Knowledge for the UNDP SDG Impact Finance initiative (UNSIF), where he led research to improve the analytical framework for social impact investing; was a member of Groupe d’Experts de la Commission sur l’Entrepreneuriat Social (GECES) of the European Commission to advise on its Social Business Initiative. Currently part of the OECD expert group on social impact investing; Senior Fellow of the Finance Innovation Lab; and Adviser to several organisations.

Was invited by civil society organisations, academia, governments and the media across Europe, Asia and USA to speak on social impact investing. Has guest lectured at the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge; advised HM Treasury on EU social investment regulations; was invited to submit evidence for alternative finance to the UK’s Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards; been asked by the UK Cabinet Office to represent the UK on social investment at EU level; was invited by US Secretary of State to be a plenary panelist at the Global Impact Economy Forum in 2012.

2011, he co-authored ‘Making Good in Social Impact Investment: Opportunities in an Emerging Asset Class’.

Holds an MBA specialising in entrepreneurship and project management, writing his dissertation on data interoperability standards and collaboration principles in the building design industry. He started his career as an architect and project manager for multidisciplinary design teams, and development leader for public and private sector construction projects. Was the founding Chair of Friends of the Crystal Palace Subway, a community-led initiative to reopen a historic community asset to the public.

Ferdi: What do you mean with the “internet of impact?”

Karl: A few things… the original term was coined when I was leading an OECD working group on data interoperability standards for social impact investing. We realised that we needed an exciting idea to keep global practitioners motivated to work on data interoperability. So the answer to the question “why are we doing this?” was “because we are creating the ‘Internet of Impact’ “.

The term stuck because it resonates on many levels.

Firstly, technical aspects of data interoperability standards and protocols are at the heart of making the web so universal and ubiquitous … the term is therefore a good reminder that strategic investment in data interoperability and enabling infrastructure (which often seems lacklustre and technically complicated) enables tremendously exciting downstream value if done correctly.

Secondly, there is a reference to democratic governance and ownership – one of the reasons the web is so successful is because it is a public commons that is accessible to everyone on the same terms. We’ve seen from the debates about net neutrality just how important these principles are, and how much they are valued by the users of the web, and sometimes challenged by parties with vested interests.

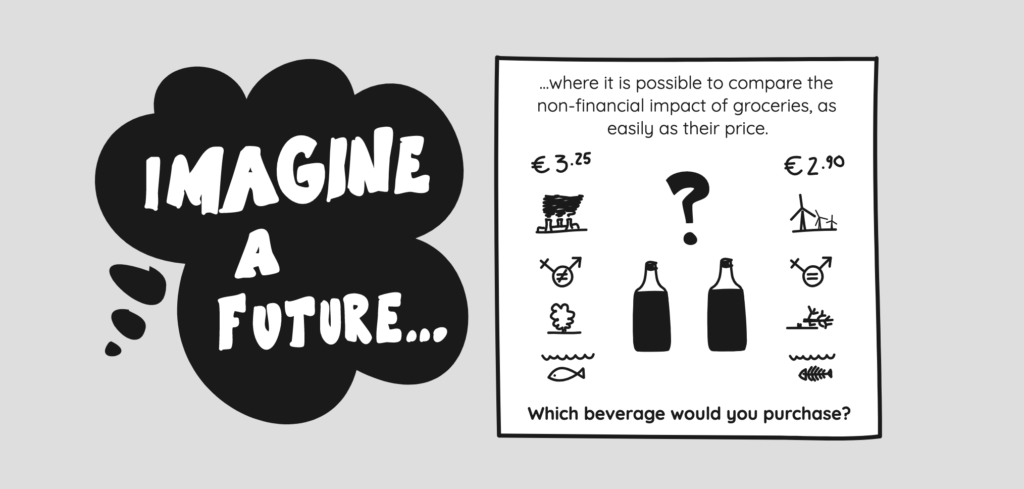

Thirdly, the term creates a bold aspiration that invites people to imagine “what if…”. In the 1980s it would have seemed impossible to have a compact smart phone in our pockets that would enable all the things that our smart phones do. Even science fiction writers from that time would often prefix their visions by saying that the kind of technology would probably not be possible, but just imagine a world if… in reality, the technology has surpassed peoples’ wildest imaginations and made those fictional narratives – and even the unimaginable – a reality.

In the context of understanding our collective impact on people on planet, in other words how business and financial activities affect our social and ecological domains – the notion of an Internet of Impact invites people to be bold and creative when imagining how to solve the data challenges we currently face. The development of the web has shown that often the only constraint has been a lack of creativity and imagination. Equally it has taught us that we should be extremely vigilant about how fast and radical some changes may be. We should be less worried about whether something could be possible or not, it is probably prudent to assume it will be possible at some point – therefore the more serious challenge is to make sure we anticipate enough about such an unknowable future, so that we put in place appropriate rules and guardrails early enough.

As much as the term should inspire creative thinking, it should also remind us of our responsibilities to manage unintended consequences as much as possible.

Ferdi: Why do we need to rethink the way we collect, store and process data to enable such an “internet of impact?”

Karl: All of our individual actions ultimately roll up to form a collective picture that is the summation of our combined efforts – it is a moving picture that keeps changing.

One of the biggest barriers to developing data solutions for impact is the prism through which we view the problem. Often (see pg 22 & 23 of this report) people suggest that they need to aggregate more data, and that we need more data platforms, or bigger data platforms, or more universal data platforms.

But all of those statements think of digital data stores like electronic filing cabinets. This assumes that for someone to have access to data, they need to make a copy of the data and put it in their data store, or move data from one data store to another that they have control over, eventually amassing a huge data store with all the data in one place.

But this is cumbersome, costly, inefficient, and paradoxically results in data that are often fragmented, duplicated, inconsistent – and typically never available in real-time because so much work needs to go into cleaning the data to make it useful. The solutions are almost more complicated than the problem – and they certainly don’t lend themselves to scaling well without centralising all the data to take advantage of economies of scale, but that in turn means that the only viable solution would be a monopoly or at best oligopoly.

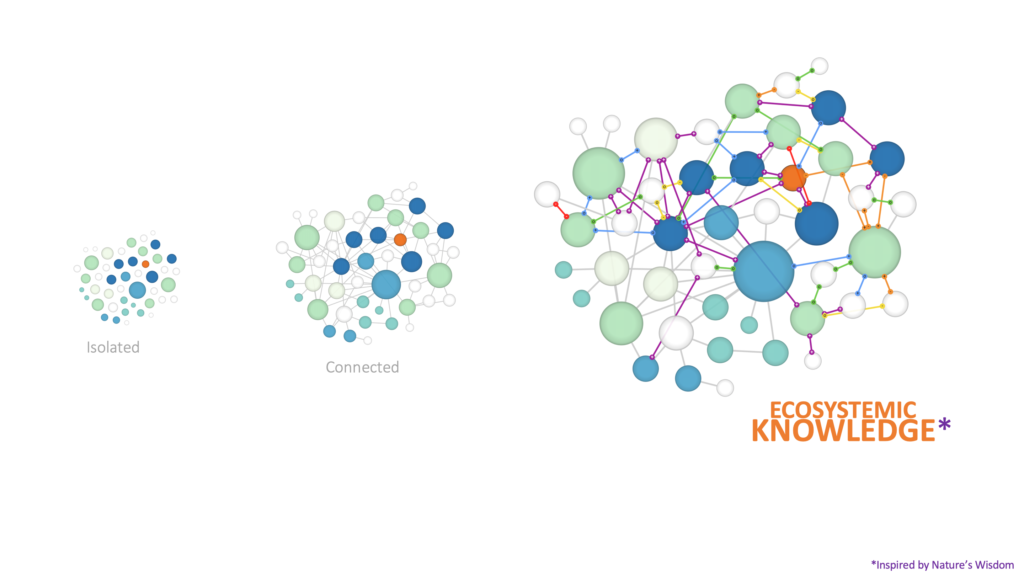

However new principles of Linked Data are very promising because they totally upend this paradigm – instead of moving or copying the data we need, we can link to the source directly. This paradigm inversion elegantly addresses a number of issues:

- In terms of the need to understand impact per se, the Linked Data approach is more aligned with what is happening in the real world. Every individual person or organisation creates impact through their mercantile actions and financial decisions. The summation of our individual actions forms the collective picture of the whole. Linked Data protocols enable us to work effectively with distributed and decentralised data that reflects this reality.

- Individual people and organisations rightfully also own the data about the impact they have. Distributed systems allow them to exercise their ownership rights through full control, access, and possession of their data. (Incidentally these OCAP principles are enshrined in Canadian First Nations requirements for how all their data are handled).

Once the interoperability challenges of distributed systems have been addressed, they are more empowering and accessible than centralised systems, especially for micro actors and diverse audiences.

Ferdi: You are a big fan of the SOLID project. What is so special about it? Why should more people be made aware of it?

Karl: There are a number of initiatives and technologies that provide distributed solutions, or aim to innovate in that arena. e.g. Blockchain and related distributed ledger technologies (DLT’s). However, they tend to be walled gardens in their own right and require people to adopt a playbook of rules or approaches – just think of Blockchain requiring miners, proof of work/ stake, ICOs, etc.

The SOLID project is different because it builds upon Linked Data principles and is an extension of the core web protocols. It thereby enables full interoperability with the whole web rather than a specific subset of the web. These protocols are open and extensible in the same way that the other stack of web protocols are.

SOLID is also a strategic enabler because it shows people and organisations how they can can store their data in data pods to make the most of Linked Data. These show how distributed data can be interconnected seamlessly with each other, and integrated with cloud software solutions.

This is radically disruptive because it creates three markets where there is currently typically only one.

- Currently users of a cloud service have no choice about where their data are stored – your data in Facebook (or whatever other cloud solution provider) are stored on their servers, and you have to accept that as a pre-condition to use their service. With SOLID there can be a dedicated and separate market for data storage (you choose to store your data where you want, whether in a secure data bunker, or on a portable device in your living room, or in a data center in the cloud) – then connect it to the service you are interested in using.

- There’s another separate market for the software services that interact with your data and provide you with the functionality you desire, but there is zero friction to switch to another provider or use multiple in parallel because your data are always stored in your data pod and connected to via API. i.e. you are never locked-in to a behemoth service provider just because they have your data.

- There is another market for data itself. People and companies can choose if they want their data to be totally private, and pay for that, or whether they are happy to let third parties provide them with free digital services in exchange for access to private data. People can also define different levels, some may only allow such access to their social media data whereas others may be happy giving access to personal health data from their smart watches. Importantly, this third market is totally independent from decisions people make in the other two about choice of data storage and which software services they use.

Ferdi: You have launched an initiative called “instans” – what are its aims? What makes it special/unique?

Karl: Instans is building upon the successes of the SOLID data pod technology (developed by Sir Tim Berners-Lee, founder of the web). SOLID has been designed for the general purpose of enabling people to take advantage of Linked Data. Instans is also positioned as a general purpose enabling infrastructure, but focused specifically on the use-case of impact data.

Instans overcomes (or will overcome in time) data fragmentation through real-time search of impact data. This means that people and software applications are able to find the data they need, retrieve them, and work with them in a seamless way as if they are one integrated centralised data set – even though the data are distributed across multiple data pods. In other words, the benefits of a decentralised system with the functionality of a centralised system.

In time it may even be appropriate for instans to fold into SOLID or other key web infrastructure. Instans is a non-profit and public good, therefore its governance and operating model should be that of a commons, like the rest of the web’s infrastructure.

Ferdi: How do you see a federated data strategy succeeding against the big data supremacy of state and corporate owned datasets?

Karl: I would challenge the inference in the question that state and corporate actors would have to loose in order for individuals to benefit from a distributed (federated) data solution. It can be a win-win that is mutually beneficial to all. State and corporate actors will be able to negotiate access to the same data they currently seek access to – and probably even more -, it will just need to be done in an open way that acknowledges a fairer social and commercial contract between the parties. In some areas regulation and legislation may also be appropriate to enforce access to pieces of data.

They will probably even get more benefits than they currently have because if people are confidence and comfortable having more private data about themselves and their companies in their data pods, then there is a more valuable trove of data out there for analysis – assuming access can be negotiated as part of a social contract. This opens up tremendous opportunity to harness these data for machine learning, AI, and so on. It may be counterintuitive, but distributed data may actually benefit state and corporate actors if they are able to adapt to the new paradigm.

Ferdi: What are some of your immediate needs? How can my readers help you and the “instans” mission?

Karl: Technical resources, or money to hire technical resources… We need to showcase the technology working with real-world users so that there is something to make the vision tangible, to build more enthusiasm and energise people so that they can see why it is worth backing instans.

Detailed description of Digital Capability Framework Here (Ferdi van Heerden, 2012 unpublished)