A special word of thanks to John for sharing his insights and perspective with us. Here is some background on him and the complete interview.

Introduction

I was born and raised in Niue, (the Rock of Polynesia), and grew up in the village of Tuapa Uhomotu with my four siblings, raised by my mum and my grandparents. It was normal to grow up in a household with cousins, uncles and aunts. My grandparents and my mother were the biggest influence in my formative years. My mum had 12 brothers and sisters and the first of her siblings to study at university, she was a teacher. She later followed the family tradition, attending theological training at PTC (Pacific Theological College) in Fiji. She was the first female Minister in Niue at a time when this was the exclusive domain for men. Watching the resistance to change from some parts of the church and the community was frustratingly fascinating, it brought out the best and worst in people.

Growing up on The Rock you’re not good at just one thing because you are expected to take part in everything. Whether or not you are good at dancing, you are expected to be part of the dance group. Whether you can play rugby or soccer, or volleyball doesn’t matter, you are just expected to play because there’s no one else. You’re not an expert in one thing, but you know a little about most things. Conforming to norms was expected and these don’t really change over time, things were done a certain way. I didn’t really like that because I wanted to do things my way and I did. Growing up we were always told how to behave and follow strict village rules and norms. There is always an expectation to be respectful and the inherent duty of care for the family. This meant doing things because that’s what society expected, not necessarily what we wanted to do.

Business had an early influence on my life as I grew up working for my grandfather in the family business, which inspired me to study business. As part of my international business major, I worked in Melbourne for a communications firm and an energy company.

Outside of work, my interests are fairly creative – I contribute to my community and work with established organisations to capture the cultural and traditional knowledge from our elders “matua” to pass on to the younger generations. When I was living in Niue I was a youth leader for over 10 years, choreographed and taught traditional and contemporary dances and songs. Traditional performing arts like the Niuean language maintains my identity and my ancestral links to Niue and my ancestors.

1. What do you think are some of the most common misconceptions about respect? Is there a specific pacific island perspective on this?

The Niuean word for respect is “Lilifu” and depending on the context “lilifu” is also honour, status, and humility. The act of respect is “Fakalilifu” which means to give or receive respect. In the Pacific world view, respect is based on our collective mindset and values, and sustained by cultural norms. This perspective is told from the Niuean view. Respect is manifested similarly across the Pacific but each Pacific Island will have its own nuanced values unique to its culture. In the Tongan culture, respect between a brother and a sister is shown by the practice that a male past puberty cannot be in the same room as his sister or female cousin, and the oldest sister of the brother has the highest social ranking in the family.

Respect is a value that some Pacific Islands cultures practise to maintain social structures and systems. These values in the context of community life including-

- Ancestors and the knowledge transfer,

- cultural and genealogical ties,

- family, church and village,

- the natural environment – the land, sky and sea,

- spiritual, cultural, social systems and structures,

In the Pacific world view respect is one of the pillars in Pacific cultures, respect is weaved through every layer of the cultural, social, spiritual, the physical fabric of society. It holds traditions and cultural knowledge firmly in the minds and daily routines of the community. A system of knowledge transfer from elders passing on knowledge to the younger generations through storytelling, traditional activities and events, festivals.

Respecting the elders was a natural order of things in the village setting. The silver-haired wise-elder, the fountain of knowledge and recipient of the cumulative knowledge passed down through time. They (the elders) have lived experience of significant events in their lifetime, from natural events like cyclones and droughts to community events and knowledge on sustainable food gathering, farming and fishing methods.

I grew up with traditional & cultural values of the roles each individual play in the community e.g. “kids are seen and not heard” and “speak when you are spoken to” so when you are in and around the workplace, your boss and your older work colleagues are the ones that do the talking and you listen. So not speaking up at work can be misinterpreted as

- shy, timid

- doesn’t have good ideas or is not bright enough.

In the Pacific world view, the younger employee learns from the elders and their managers in the workplace. The employee shows respect by listening and not challenging their manager or elders authority in the workplace. This is the opposite of the individualistic behaviours highly valued in the workplace.

Respect is used with humility as a core cultural value in the Pacific, where one should not be too boastful of their ability and achievements. A Maori proverb ‘Kāore te kumara e kōrero mō tōna ake reka’ which translates – the kumara (sweet potato) does not speak of its own sweetness. People around you should talk of your achievements and ability, and one does not boast about their own abilities and achievements. This cultural value is misunderstood by those who don’t understand the Pacific worldview.

Here is a scenario that happens in most workplaces here in NZ, a Pacific employee takes an entry-level role. The employee works hard and diligently, with the view the manager/employer will see the hard work and reward them with a promotion.

There are two very different mindsets in play, one of the employee and that of the employer. The employee will not put their hand up for promotion, rather will wait for the manager or someone in authority to notice their hard work. The employer will see a hardworking and loyal worker who has been working in the same role for say 5 to 10 years or even longer, and see the employee has shown no initiative for promotion. The employer concludes the employee is happy in their role. These scenarios play out in many workplaces with the Pacific employee and employers of Pacific employees.

This event played out in the earliest recorded history of Niueans with Europeans. Captain Cook, sailed and chartered the islands in the Pacific ocean. Cook noted in some of his voyages of using local Polynesian navigators, Tupaia’s knowledge of the star navigation technique helped Cook to reach some of the most remote islands. Cook charted and named some of the Islands, he charted the Cook Islands after himself, and Tonga the Friendly Islands. He sailed past and chartered Niue on 20th June 1774 sailing from Raiatea, Tahiti in search of the Great Southern Continent. Cook tried to make three separate landings in the north and the western coasts of the island. The warriors greeted him with the “takalo.” A challenge to see whether the visitors come as friends or foe. The visitors account, the islanders charged with the “ferocious of wild boars.” The local stories of warriors in the traditional kit, with the “kafa” finely plaited hair girdles around their waist, rounded throwing stones attached and holding throwing spears and cleaving clubs, with blackened faces and bodies with charcoal, and dye stained teeth from the magenta sap from the “futi hula hula” a variety of banana tree. Cook and his men misinterpreted this as hostile reception with inhospitable people, and charted Savage Island and promptly sailed on. The name Savage Island protected Niue for a while from the slave Trading Ships that frequent the Pacific to kidnap people for the lucrative slave-trading markets in the Pacific rim.

2. Last year we spoke about how some ancient wisdom about nature and society was dismissed for a long time as uneducated and outmoded. Now we realise that so much of how the generations before adopted as best practice is indeed the way to create and sustain a liveable planet. How should we think about this pendulum? How do we prevent a dominant dogma from preventing respect for deeper wisdom? How can we kindle a new respect for the old?

Indigenous communities survived generations living in harmony with their environment. These communities have learnt through the generations the impact of human unsustainable activities on the environment, e.g. Rapa Nui of Easter Island.

I grew up surrounded by the knowledge handed down over many generations of how to live sustainably with the limited resources on a small remote island.

Limited natural resources, limited to no surface fresh water, and limited farming land. Niueans learnt to balance their impact with the resources on a remote island to grow and gather food to sustain them, whether that be how to toil and farm the land, restrictions or periods of “fono tapu” or no-take areas so birds and fish stocks can recover.

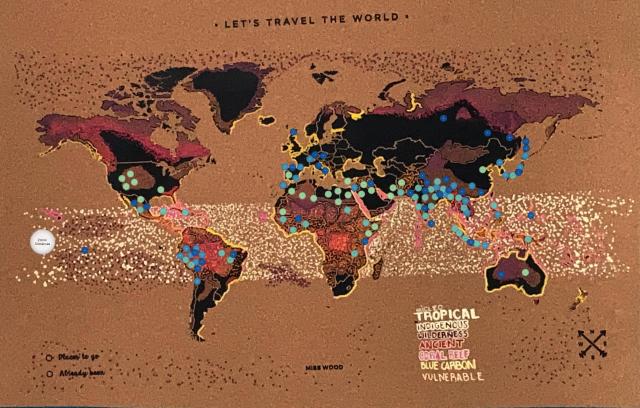

Respecting the land, sea and sky is about survival for the people in the Pacific. The land, sky and sea are the food baskets that sustained generations of our people. Our values see our role as caretakers “leveki” for these resources to provide future generations access to the same food resources. The pace and rhythm of community life in the Pacific is dictated by the changing seasons, for most places the different seasons mark the arrival of migratory birds and certain species of seasonal fish.

I didn’t really appreciate the value of traditional knowledge growing up, the education system focused on values different to my cultural values (traditional knowledge). Like many of my peers, I have come to appreciate the value of cultural knowledge as an adult. Growing up with grandparents, I was very fortunate to learn about the traditional knowledge of my culture. The skills and knowledge of growing and planting food depending on the season or time of the day, knowledge of natural remedies to treat different kinds of ailments, knowledge of gathering, preparing and cooking traditional food etc.

The value of this knowledge is priceless and I wished this was written down when I had the opportunity with my grandparents. The dilemma with our traditional and cultural knowledge, our genealogies, stories and songs are in the heads of older generations and are not usually written down.

3. Respect is in many ways a reflexive phenomenon (root meaning: look back at https://www.etymonline.com/word/respect). The respect you give is what you receive. Yet many people relax in the formal/structural titles and positions that afford respect to them, without respecting the ones they serve or have given them that position. How can we ensure that respect flows both ways?

The cultural and traditional norms I grew up on did have formal/structural cultural titles and positions. Respect is earned, this is weaved throughout many aspects of society. Niue doesn’t have the cultural and social structures prevalent in other Pacific Islands. Early anthropological studies observed limited social structures in place and the egalitarian nature of the people based in nascent family groups. In practice today, the job title provides some recognition of status. The lack of social structures means anyone can choose where they end up regardless of where they started. The harder you work for your family and community, the higher your status. With the introductions of Christianity and western structures in employment, a person’s title can earn them the respect, however real and valued respect is earned through one’s hard work to contribute back to the community.

4. In many ways blind respect becomes a hindrance to progress and adaptation. How can we keep respect vital to ensure communities stay adaptive?

Yes when respect is used as a tool to repress, instil fear, will hinder progress and adapting to changes in society. This is the dark side of respect when people in minority and vulnerable communities are not taking part or given the opportunity and support to prosper and flourish.

When respect is used to keep people focused and living in the past, when we should use the learnings of the past to anchor and light the way for the future. When respect is used to keep people from moving forward is when we see great disparities in income and wealth.

Is it the risk-averse nature of people to fear the unknown? It is easier to understand and embrace what people know and are familiar with. It takes courage and a learning mindset to embrace change and the unknown nature of what is ahead.

5. What do you think is the most surprising way in which respect is lived and experienced in the communities you deal with?

Not surprising, I am more intrigued when respect is lived and experienced as an entitlement and sometimes used as a mask. Personally, the way leadership is approached by the different communities is intriguing, when respect is based on people’s titles and status, regardless of ability. I mentioned earlier I grew up in a culture which doesn’t look to social structures and titles as a birthright, respect is based on one’s experience, knowledge, community work and character. You respect your elders because of their knowledge and experience. I see respect in its pure and simple form, in communities in simple and basic living conditions with limited or no assets, and are happy and content with their lives.

6. What are some of the examples where respect has been used to foster a stronger, more inclusive community?

When vulnerable and most disadvantaged communities are given the tools and resources to determine their own solutions to the challenges they face every day. When safe spaces enable them to get support and resources and be involved in determining the problems to be addressed and the solutions to those problems. These communities have a wealth of knowledge of what works and they have tried these solutions. Working closely with the communities builds trust, but more bespoke solutions that have a higher possibility of solving the complex challenges in the community. They should be part of designing a system that is going to affect their livelihood, health and wellbeing.

7. What did I miss? What would you like to ask?

To me respect is deeply a personal value, it is core to everything we do. I grew up on stories about the spiritual world, for example in some Pacific cultures wearing red or whistling at night in the village is not allowed. This is illogical if you went through our western influenced education system. Why not, what is the science behind it? While I don’t understand why I was told not to do that, I have a healthy respect for it. There are some things that science and logic can explain away.

The opposite of respect is not necessarily the absence of it. Admiration and reverence are how we describe respect, and the absence of admiration or reverence does not necessarily mean disrespect. But is ignorance a great defence, it is disrespectful to play the ignorance card when one has the opportunity to be open-minded and learn. Respect is core values, connected to our emotions so when people feel disrespected, it is the acts of others not aligned with their core values.

BIO

A childhood grounded in culture, tradition, and business with strong values focused on hard work, respect, integrity and self-awareness have guided John Christopher Faitala throughout his career. With education qualifications in management, international business and marketing, including an MBA, and a creative and entrepreneurial spirit, John has worked for central government agencies in Niue and New Zealand, as well as local government and the private sector in Niue, Melbourne and Auckland. John brings his unique experience and insights to his work at the Pacific Business Trust, a Pacific Economic Development Agency in New Zealand. John uses the Talanoa tool and the Kakala framework (Pacific frameworks) in the Pasifika Innovation Approach, a co-design framework to engage Pasifika communities in New Zealand and the wider region.